Hash & Encryption

Hash and Encryption: Key Concepts and Differences

In cybersecurity, hashing and encryption are essential techniques for data protection. While often confused, they have fundamental differences in their purpose and operation.

A hash is a one-way function that transforms arbitrary-length data into a fixed-length hash value or digest. The crucial point is that you cannot reverse a hash to recover the original data. This makes it useful for password storage and data integrity verification.

Encryption, on the other hand, is a technique to ensure confidentiality by transforming data into ciphertext using a specific key. Encrypted data can be reverted to its original form using the correct decryption key.

Generally, hash operations are faster than encryption operations. However, certain hash functions used for password hashing (Key Derivation Functions) are intentionally designed to be computationally expensive to make brute-force attacks more difficult.

Types of Hash Functions and Selection

Common hash functions include MD5, SHA-1, SHA-256, and SHA-512. Among these, MD5 and SHA-1 have known security vulnerabilities (susceptibility to collision attacks) and are no longer recommended for security purposes.

For password hashing in particular, you should use Key Derivation Functions (KDFs) rather than simple hash functions. Popular KDFs include PBKDF2 (Password-Based Key Derivation Function 2), bcrypt, and scrypt. These effectively use a salt and allow for adjusting the number of iterations, thereby increasing resistance against brute-force and rainbow table attacks.

A good cryptographic hash function must satisfy three critical properties:

- Pre-image Resistance: It should be computationally infeasible to find the original input from a given hash value. (One-way property)

- Second Pre-image Resistance: It should be computationally infeasible to find a different input that produces the same hash value as a given input.

- Collision Resistance: It should be computationally infeasible to find two different inputs that produce the same hash value.

Two Approaches to Encryption: Symmetric-key and Asymmetric-key

There are two main types of encryption methods:

1. Symmetric-key Encryption

Symmetric-key encryption uses the same encryption key for both encrypting and decrypting data. Its advantage lies in its speed, making it efficient for encrypting large volumes of data. However, it introduces the key distribution problem, where both the sender and receiver must securely share the same key.

- Examples: DES (Data Encryption Standard, no longer secure for most uses), 3DES (Triple DES), AES (Advanced Encryption Standard), Blowfish, Twofish, RC4 (stream cipher).

2. Asymmetric-key Encryption

Asymmetric-key encryption uses a pair of different keys for encryption and decryption: a public key and a private key. The public key can be openly distributed, while the private key must be kept secure by its owner. Data encrypted with a public key can only be decrypted by its corresponding private key. Conversely, data signed with a private key can be verified with its public key. While it simplifies key distribution, it is slower than symmetric-key encryption.

- Examples: RSA, ElGamal, DSS (Digital Signature Standard), ECC (Elliptic Curve Cryptography), Diffie-Hellman (primarily used for key exchange).

MAC and HMAC: Message Integrity and Authentication

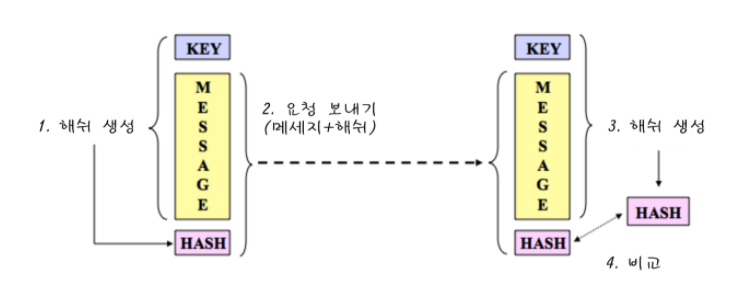

A Message Authentication Code (MAC) is a cryptographic technique used to ensure the integrity and authentication of a message. A MAC does not provide confidentiality for the message itself. Instead, it focuses on verifying that the message hasn’t been tampered with during transmission and proving that the sender is who they claim to be. This is more efficient than encryption when a message’s confidentiality isn’t critical, but its authenticity and integrity are.

The fundamental principle of MAC operates under the premise that both the sender and receiver possess a shared secret key.

- Sender: Calculates a MAC value ($C_K(M)$) using the message ($M$) and the shared secret key ($K$). This MAC value is then appended to the message and sent.

- Receiver: Upon receiving the message, recalculates the MAC value using the received message and their own shared secret key in the same manner.

- Comparison: The receiver compares their calculated MAC value with the MAC value sent by the sender. If the two values match, it confirms that the message has not been altered during transmission and that the sender is a legitimate user possessing the correct key.

MACs are not encrypted, so there’s no concept of decryption. Integrity and authentication are verified solely by comparing the digests generated with the same key and function.

HMAC: Hash-based Message Authentication Code

HMAC (Hash-based Message Authentication Code) is a type of MAC that generates a message authentication code based on cryptographic hash functions like MD5, SHA-1, and SHA-256. HMAC can be thought of as “keyed-hashing” since it requires a key for message authentication. HMAC uses a symmetric key, while a Digital Signature uses an asymmetric key.

Here’s how HMAC works:

- Key and Message Combination: The sender combines the message and the shared secret key in a specific way.

- Hash Function Application: The combined data is then fed into a hash function to produce the HMAC digest.

- Transmission and Verification: This digest is sent along with the message. The receiver then generates a digest in the same manner and compares it to the received digest.

- Advantages of HMAC: It’s impossible to tamper with a message without the key, and it provides significantly stronger security than merely using a standard hash function. This is because HMAC incorporates mechanisms to protect the MAC from vulnerabilities inherent in the hash function itself (e.g., collision attacks).

- Lack of Confidentiality: While HMAC guarantees message integrity and authentication, it does not protect the confidentiality of the message itself. If the confidentiality of the original message is crucial, you should use secure transmission channels like HTTPS or encrypt the message in addition to using HMAC.

Defending Against HMAC Replay Attacks

HMAC can be vulnerable to Replay Attacks. An attacker might intercept a legitimate message containing an HMAC and then re-transmit it later to trick the system. For example, a captured car unlock signal could be replayed to unlock the vehicle.

To defend against such vulnerabilities, consider these methods:

- Timestamp: Include a timestamp in the message indicating the current time, and use it when calculating the HMAC. The receiver then verifies that the timestamp is within a valid time window, rejecting any messages that are too old.

- Random Nonce: Incorporate a randomly generated number (a Nonce) that is used only once into the message, and use it when calculating the HMAC. The receiver checks if this nonce has been used before, preventing replays.

The Relationship Between Encryption and Compression: Security Implications

Whether to compress data before encryption or encrypt it before compression is a critical security concern. The wrong order can lead to severe vulnerabilities.

Compress Then Encrypt: Vulnerability to Side-Channel Attacks

If you compress data first and then encrypt it, you can become vulnerable to side-channel attacks, specifically compression oracle attacks. Notable examples include CRIME and BREACH attacks against SSL/TLS.

The principle of these attacks is as follows:

- Compression algorithms reduce data size by finding repeating patterns.

- An attacker can observe the size changes in encrypted data to infer information about the original data. For instance, if an attacker injects a specific string and observes a significant reduction in the size of the compressed data, they can infer that the string existed in the original data. This allows for brute-force guessing of sensitive information, such as session cookies.

Encrypt Then Compress: Efficiency Challenges

Conversely, if you encrypt data first and then compress it, it’s more secure from a cryptographic standpoint. Encryption maximizes data randomness and destroys statistical patterns. However, in this scenario, compression efficiency significantly degrades. Since encrypted data is already highly random, compression algorithms find it nearly impossible to identify patterns and reduce the data size.

Conclusion: Prioritizing Security in Compression/Encryption Strategies

Generally, compressing data before encryption is vulnerable to compression oracle attacks and should be avoided. If both operations are necessary, performing encryption first and then attempting compression is more secure. However, be aware that you shouldn’t expect significant data size reduction from compression in this case.

In many scenarios, if security is the top priority, you should avoid combining compression and encryption, or consider handling them independently at different service layers. If the benefits of compression (primarily storage space savings and transmission efficiency gains) do not outweigh the security risks, it is more prudent to forgo compression for security reasons. Many modern systems have seen substantial reductions in network bandwidth and storage costs, making security a far greater priority than the benefits gained from compression.

What does it mean to handle independently at different service layers?

This refers to performing necessary functions independently at specific layers of an application. This minimizes the propagation of security vulnerabilities from one layer to another and allows for effective implementation of a Defense in Depth strategy.

- Application Layer: This layer focuses on protecting the confidentiality and integrity of the data itself. For example, sensitive user information to be stored in a database or important files uploaded by users can be encrypted directly within the application logic. This encryption helps prevent data leaks if the file system or database is compromised. At this stage, the data might still be in its uncompressed, original state, and encryption would already reduce patterns, making subsequent compression less efficient.

- Transport Layer: This layer handles the security of data as it’s transmitted over a network. Protocols like TLS/SSL (Transport Layer Security / Secure Sockets Layer) are prime examples. TLS/SSL encrypts all data in transit, protecting it from man-in-the-middle attacks or eavesdropping. A critical point is that disabling compression in TLS/SSL settings is strongly recommended. This is to prevent compression oracle attacks like CRIME/BREACH, as discussed earlier. This applies to all data being transmitted, regardless of whether it was already encrypted at the application layer.

- File System/Storage Layer: This layer enhances the physical security of stored data. Disk encryption (e.g., BitLocker, dm-crypt, AWS EBS Encryption) encrypts entire hard drives or specific partitions, ensuring data protection even if the physical disk is stolen. Compression at this layer is generally not used due to performance concerns or security implications.

By ensuring each layer independently achieves its security objectives, you can minimize issues where compression in one layer impacts encryption security in another. For instance, sensitive information to be stored in a database would be encrypted at the application level, and when transmitted from the web server to the client, TLS/SSL encryption would be used with compression disabled. This approach helps achieve data confidentiality and integrity from a Defense in Depth perspective, allowing for optimal security configurations tailored to each layer’s purpose.

Salted Password Hashing: Secure Password Management

Securely storing user passwords is crucial for protecting user accounts in the event of a data breach. The main reason for using hash functions is to make it difficult to recover the original password if the hashed version is leaked. Hashing is characterized by its one-way nature and fast computation speed.

However, simply hashing passwords is not enough. The following attacks exist:

1. Password Cracking Attacks

- Dictionary Attack: This attack involves hashing a pre-prepared list of common words or phrases (a dictionary file) and comparing these hashes to the stored hash values in the database.

- Brute-Force Attack: This attack attempts every possible character combination for a given length and compares its hash to the target hash value. While computationally very expensive, it can eventually succeed with sufficient time and resources.

- Lookup Table Attacks: Attackers pre-compute a table of hash values for numerous probable passwords. They then use this table to quickly find the original password corresponding to a leaked hash value from a database.

- Reverse Lookup Table: This involves creating a lookup table of leaked account IDs and hashed passwords from a compromised database. An attacker then hashes guessed passwords and checks if the digest exists in this pre-built table, mapping passwords to the users who use them.

- Rainbow Table: This technique addresses the storage space issue of lookup tables. It involves pre-computing and storing “chains” of hash values and their corresponding original strings. This reduces the computational effort needed during an attack to quickly find original passwords. This is an example of a Time-Space Trade-off technique.

These attacks make password cracking easier and faster. While we cannot completely prevent these attacks, we can significantly reduce their effectiveness.

2. Adding Salt: Enhancing Hashing Security

To mitigate the vulnerabilities of simple password hashing, an arbitrary piece of data called a salt is added before hashing. A salt does not need to be encrypted, and its mere presence is highly effective in neutralizing the lookup table and rainbow table attacks mentioned above. Rather than simply prepending or appending the salt to the password, it’s best to use Key Derivation Functions (KDFs) designed to securely incorporate the salt internally.

Incorrect Salt Usage

- Salt Reuse: Reusing the same salt for multiple users or for a user’s changed password is highly risky. This allows rainbow table attacks to become feasible again or enables the cracking of multiple account passwords simultaneously. A random salt must be generated every time a user account is created or a password is changed.

- Short Salt: If the salt’s length is too short, attackers can easily create lookup tables for all possible salt values. The salt should be at least as long as, or longer than, the output length of the hash function being used (e.g., 256 bits or 32 bytes for SHA-256).

- Double Hashing & Wacky Hash Functions: It might seem safer to mix different hash algorithms or use complex, unproven hashing methods. However, this can inadvertently create unpredictable vulnerabilities or only marginally increase the time an attacker needs for analysis, without providing fundamental security enhancements. The safest and most efficient approach is to use well-designed, vetted standard hash algorithms and recommended Key Derivation Functions (like PBKDF2, bcrypt, scrypt) according to their intended usage.

Correct Salt Usage

Secure Salt Generation: When generating a salt, you should use a Cryptographically Secure Pseudo-Random Number Generator (CSPRNG), not a simple Pseudo-Random Number Generator (PRNG).

Per-User and Per-Password Uniqueness: The salt must be unique for each user and for each password change. A new random salt should be generated whenever a user creates an account or changes their password. This salt should be at least as large as the hash digest.

Salt Storage: The generated salt should be stored in the user database alongside the user’s hashed password. The salt is not a secret and does not need to be encrypted.

Password Verification: To verify a password entered by a user, retrieve the user’s salt and hash value from the database. Then, apply the retrieved salt to the given password, hash it, and compare this result to the hash value stored in the database.

Server-Side Hashing: In web applications, password hashing must always be performed on the server side. Even if a client-side script (e.g., JavaScript) hashes the password before transmission, this does not replace secure transport channels like HTTPS, and it could make the system vulnerable if an attacker intercepts the client-side hash result. Additionally, not all browsers may support client-side scripting.

Key Stretching: Key stretching is a technique where the same hash function is applied thousands or even tens of thousands of times to generate a digest. This dramatically increases the computational cost of brute-force attacks against password hashing.

- Iteration Count Setting: The number of iterations should be set to a level that doesn’t excessively consume web server resources (e.g., within 0.2 seconds) but makes effective attacks computationally infeasible for attackers. This iteration count should be periodically increased as hardware performance improves over time.

- Use of Professional Libraries: Instead of implementing key stretching algorithms yourself, it is safer to use functions provided by well-vetted cryptographic libraries (e.g.,

PBKDF2_HMAC_SHA256with configurable iterations).

Leveraging Hardware Security Modules (HSM): Using a Hardware Security Module (HSM), such as YubiHSM, to securely manage secret keys and perform hashing operations can provide a robust defense against hash cracking that is difficult to achieve with software-only methods. Even when using algorithms like HMAC, secret key management is crucial, and HSMs are useful for physically protecting keys.

Why HSMs Offer Stronger Hash Cracking Defense Than Software:

An HSM is a physical device specifically designed to generate, store, protect, and perform cryptographic operations using encryption keys. Compared to software-based solutions, HSMs provide stronger security in several ways:

- Physical Security: HSMs are built with tamper-resistant and tamper-evident features to protect keys from physical attacks. Keys are physically isolated inside the device, making them extremely difficult to access through software exploits. In contrast, software-based keys might reside in operating system memory or on disk, increasing their vulnerability to exfiltration during a system compromise.

- Key Non-Exposure: Keys are generated and used within the HSM, and are designed never to leave the HSM. This “Zero-Exposure” principle means that even if an attacker completely compromises the surrounding system, they cannot extract the keys through memory dumps or other software techniques. Secret keys used in hashing operations are also securely stored within the HSM, preventing unauthorized access.

- Performance and Dedicated Hardware: HSMs contain dedicated hardware optimized for cryptographic operations. This allows them to perform encryption, hashing, and other cryptographic tasks much faster and more efficiently than general-purpose server CPUs executing software algorithms. This is crucial for maintaining security performance under high system loads.

- Certification and Compliance: Many HSMs are designed and certified to meet stringent security standards (e.g., FIPS 140-2 Level 3 or higher). This is essential for environments with strict regulatory compliance requirements, such as finance and government.

- Secure Auditing and Logging: HSMs generate detailed, immutable security logs of key usage and access. This provides a clear audit trail, enabling monitoring of security events and providing crucial data for forensic analysis in case of a breach.

For these reasons, HSMs are a powerful solution, either replacing or complementing software-based key management and hashing, particularly in environments handling sensitive data or requiring very high levels of security. HSMs support a wide range of cryptographic functions, including symmetric-key encryption, asymmetric-key encryption, hashing, and random number generation, all while prioritizing the secure protection of keys.

Constant-Time Comparison: When comparing hash values, the comparison function should be implemented to take a constant amount of time. This is to defend against Timing Attacks. If a comparison function checks byte-by-byte and immediately stops when a mismatch is found, an attacker could measure the time taken for each byte comparison to slowly infer the password. Some standard library functions, like

memcmp, may not guarantee constant-time comparison, so it’s important to use cryptographically secureconstant-time comparisonfunctions.

References

해시와 암호화: 핵심 개념 및 차이점

사이버 보안 분야에서 해시(Hash)와 암호화(Encryption)는 데이터를 보호하는 데 필수적인 기술입니다. 이 둘은 종종 혼동되지만, 근본적인 목적과 작동 방식에서 중요한 차이가 있습니다.

해시는 임의 길이의 데이터를 고정된 길이의 해시값(hash value) 또는 다이제스트(digest)로 변환하는 단방향 함수입니다. 중요한 점은 해시된 결과물로부터 원본 데이터를 복원할 수 없다는 것입니다. 이는 패스워드 저장, 데이터 무결성 검증 등에 활용됩니다.

반면, 암호화는 데이터를 특정 키를 사용하여 암호문(ciphertext)으로 변환하여 기밀성을 확보하는 기술입니다. 암호화된 데이터는 올바른 복호화 키(decryption key)를 사용하면 원본 데이터로 다시 복원할 수 있습니다.

일반적으로 해시 연산은 암호화 연산보다 빠릅니다. 하지만 패스워드 해싱에 사용되는 특정 해시 함수(키 유도 함수)는 의도적으로 계산 비용이 높게 설계되어 무차별 대입 공격(Brute-force attack)을 어렵게 합니다.

해시 함수의 종류와 선택

일반적인 해시 함수로는 MD5, SHA-1, SHA-256, SHA-512 등이 있습니다. 이 중 MD5와 SHA-1은 보안 취약점(충돌 공격에 취약)이 발견되어 현재는 보안 목적으로 사용을 권장하지 않습니다.

특히 패스워드 해싱에는 단순한 해시 함수가 아닌 키 유도 함수(Key Derivation Functions, KDFs)를 사용해야 합니다. 대표적인 KDFs는 PBKDF2(Password-Based Key Derivation Function 2), bcrypt, scrypt 등이 있습니다. 이들은 솔트(Salt)를 효과적으로 사용하고, 반복 횟수를 조절하여 계산 비용을 높일 수 있어 무차별 대입 공격과 레인보우 테이블 공격에 대한 저항력을 강화합니다.

좋은 암호학적 해시 함수는 다음 세 가지 중요한 속성을 만족해야 합니다:

- 역상 저항성(Pre-image Resistance): 주어진 해시값으로부터 원본 입력값을 찾는 것이 계산적으로 불가능해야 합니다. (단방향성)

- 제2역상 저항성(Second Pre-image Resistance): 주어진 입력값과 동일한 해시값을 가지는 다른 입력값을 찾는 것이 계산적으로 불가능해야 합니다.

- 충돌 저항성(Collision Resistance): 동일한 해시값을 가지는 서로 다른 두 입력값을 찾는 것이 계산적으로 불가능해야 합니다.

암호화의 두 가지 방식: 대칭키와 비대칭키

암호화 방식은 크게 두 가지로 나뉩니다.

1. 대칭키 암호화 (Symmetric-key Encryption)

대칭키 암호화는 데이터를 암호화하고 복호화할 때 동일한 암호화 키를 사용하는 방식입니다. 속도가 빠르다는 장점이 있어 대량의 데이터를 암호화하는 데 효율적입니다. 하지만 송신자와 수신자가 안전하게 키를 공유해야 한다는 키 분배(Key Distribution) 문제가 발생할 수 있습니다.

- 종류: DES (Data Encryption Standard, 현재는 보안상 사용하지 않음), 3DES (Triple DES), AES (Advanced Encryption Standard), Blowfish, Twofish, RC4 (스트림 암호)

2. 비대칭키 암호화 (Asymmetric-key Encryption)

비대칭키 암호화는 암호화와 복호화에 서로 다른 한 쌍의 키, 즉 공개키(Public Key)와 개인키(Private Key)를 사용하는 방식입니다. 공개키는 누구나 알 수 있도록 공개하고, 개인키는 소유자만 안전하게 보관합니다. 공개키로 암호화한 데이터는 해당 공개키에 해당하는 개인키로만 복호화할 수 있고, 반대로 개인키로 서명한 데이터는 공개키로 검증할 수 있습니다. 키 분배가 용이하다는 장점이 있지만, 대칭키 암호화에 비해 속도가 느립니다.

- 종류: RSA, ElGamal, DSS (Digital Signature Standard), ECC (Elliptic Curve Cryptography), Diffie-Hellman (키 교환에 주로 사용)

MAC과 HMAC: 메시지 무결성 및 인증

메시지 인증 코드(MAC: Message Authentication Code)는 메시지의 무결성(Integrity)과 인증(Authentication)을 보장하는 데 사용되는 암호학적 기법입니다. MAC은 메시지 자체의 기밀성(Confidentiality)을 제공하지는 않으며, 메시지가 전송 중에 변조되지 않았음을 확인하고 송신자가 주장하는 사람임을 증명하는 데 중점을 둡니다. 이는 메시지가 외부에 노출되어도 상관없고 인증만 필요한 경우에 암호화보다 효율적입니다.

MAC의 기본 원리는 송신자와 수신자가 공유 비밀 키(Shared Secret Key)를 가지고 있다는 전제하에 작동합니다.

- 송신자: 메시지($M$)와 공유 비밀 키($K$)를 사용하여 MAC 값($C_K(M)$)을 계산합니다. 이 MAC 값을 메시지에 첨부하여 전송합니다.

- 수신자: 수신된 메시지와 자신이 가지고 있는 공유 비밀 키를 사용하여 동일한 방식으로 MAC 값을 다시 계산합니다.

- 비교: 수신자가 계산한 MAC 값과 송신자가 보낸 MAC 값을 비교하여 일치하는지 확인합니다. 두 값이 일치하면 메시지가 전송 중에 변조되지 않았고, 송신자가 해당 키를 소유한 정당한 사용자임을 확신할 수 있습니다.

MAC은 암호화된 형태가 아니기 때문에 복호화라는 개념이 없습니다. 오직 키와 함수를 통해 생성된 다이제스트를 비교함으로써 무결성과 인증을 확인합니다.

HMAC: 해시 기반 메시지 인증 코드

HMAC(Hash-based Message Authentication Code)은 MAC의 한 종류로, MD5, SHA-1, SHA-256과 같은 암호학적 해시 함수를 기반으로 메시지 인증 코드를 생성하는 방식입니다. HMAC은 메시지 인증을 위해 키가 필요한 “키드 해싱(keyed-hashing)”이라고도 할 수 있습니다. HMAC은 대칭키를 사용하고 Digital Signiture는 비대칭키 방식을 사용합니다.

HMAC의 작동 방식은 다음과 같습니다.

- 키와 메시지 결합: 송신자는 메시지와 공유 비밀 키를 특정 방식으로 결합합니다.

- 해시 함수 적용: 결합된 데이터를 해시 함수에 넣어 HMAC 다이제스트를 생성합니다.

- 전송 및 검증: 이 다이제스트를 메시지와 함께 전송하고, 수신 측에서는 동일한 방식으로 다이제스트를 생성하여 받은 다이제스트와 비교합니다.

- HMAC의 이점: 키 없이는 메시지 위변조가 불가능하며, 일반적인 해시 함수만을 사용하는 것보다 훨씬 강력한 보안을 제공합니다. 이는 해시 함수 자체의 취약점(예: 충돌 공격)으로부터 MAC을 보호하는 메커니즘을 포함하기 때문입니다.

기밀성 부족: HMAC은 메시지의 무결성과 인증을 보장하지만, 메시지 자체의 기밀성을 보호하지는 않습니다. 원문 메시지의 기밀성이 중요하다면, HMAC과 함께 HTTPS와 같은 안전한 전송 채널을 사용하거나 메시지 자체를 암호화해야 합니다.

HMAC의 재전송 공격(Replay Attack) 방어

HMAC은 재전송 공격(Replay Attack)에 취약할 수 있습니다. 공격자가 정당한 HMAC이 포함된 메시지를 가로채서 나중에 다시 전송함으로써 시스템을 속일 수 있는 공격입니다. 예를 들어, 차량 잠금 해제 신호를 캡처했다가 나중에 다시 보내는 방식이 있습니다.

이러한 취약점을 방어하기 위해 다음과 같은 방법을 사용합니다.

- 타임스탬프(Timestamp): 메시지 내에 현재 시간을 나타내는 타임스탬프를 포함하고, HMAC을 계산할 때 이 타임스탬프를 함께 사용합니다. 수신 측에서는 메시지를 받은 후 타임스탬프가 유효한 시간 범위 내에 있는지 확인하여 너무 오래된 메시지를 거부합니다.

- 랜덤 논스(Random Nonce): 한 번만 사용되는 임의의 숫자(Nonce)를 메시지에 포함하고 HMAC을 계산합니다. 수신 측에서는 이 논스가 이전에 사용된 적이 있는지 확인하여 재전송을 방지합니다.

암호화와 압축의 관계: 보안에 미치는 영향

데이터를 암호화하기 전 압축을 할지, 아니면 압축하기 전 암호화를 할지는 중요한 보안 문제입니다. 잘못된 순서는 심각한 취약점을 야기할 수 있습니다.

압축 후 암호화: Side-Channel Attack 취약성

데이터를 먼저 압축하고 그 후에 암호화하면 측면 채널 공격(Side-channel attack), 특히 압축 오라클(Compression Oracle) 공격에 취약해질 수 있습니다. 대표적인 예시로 CRIME 및 BREACH와 같은 SSL/TLS 공격이 있습니다.

이러한 공격의 원리는 다음과 같습니다.

- 압축 알고리즘은 데이터 내의 반복되는 패턴을 찾아 크기를 줄입니다.

- 공격자는 암호화된 데이터의 크기 변화를 관찰하여 원본 데이터에 대한 정보를 추론할 수 있습니다. 예를 들어, 공격자가 특정 문자열을 삽입했을 때 압축된 데이터의 크기가 크게 줄어든다면, 해당 문자열이 원본 데이터 내에 존재했음을 유추할 수 있습니다. 이를 통해 민감한 정보(예: 세션 쿠키)를 브루트 포스(Brute-force) 방식으로 추측할 수 있습니다.

암호화 후 압축: 효율성 문제

반대로 데이터를 먼저 암호화하고 그 후에 압축하면 보안 측면에서는 더 안전합니다. 암호화는 데이터의 통계적 패턴을 파괴하고 무작위성을 극대화하기 때문입니다. 그러나 이 경우 압축 효율성이 크게 떨어집니다. 암호화된 데이터는 이미 무작위적이기 때문에 압축 알고리즘이 패턴을 찾아 크기를 줄이는 것이 거의 불가능해집니다.

결론: 각 서비스 레이어에서 독립적 처리 고려

일반적으로 데이터를 압축하고 암호화하는 것은 압축 오라클 공격에 취약하므로 피해야 합니다. 만약 두 가지 작업이 모두 필요하다면, 암호화를 먼저 수행하고 그 후에 압축을 시도하는 것이 보안상 더 안전합니다. 다만, 이때는 압축으로 인한 크기 감소 효과를 크게 기대하기 어렵다는 점을 인지해야 합니다.

많은 경우, 보안이 최우선이라면 압축과 암호화를 동시에 사용하지 않거나, 각 서비스 레이어에서 독립적으로 처리하는 것을 고려해야 합니다. 압축을 통해 얻을 수 있는 이점(주로 저장 공간 절약 및 전송 효율 증가)이 보안 위험보다 크지 않다면, 보안을 위해 압축을 포기하는 것이 더 합리적인 선택입니다. 많은 현대 시스템에서는 네트워크 대역폭이나 스토리지 비용이 크게 절감되면서, 압축으로 얻는 이점보다 보안의 중요성이 훨씬 커졌습니다.

각 서비스 레이어에서 독립적 처리란?

이는 애플리케이션의 특정 계층(Layer)에서 필요한 기능을 독립적으로 수행하는 것을 의미합니다. 예를 들어:

- 애플리케이션 계층(Application Layer): 사용자가 업로드하는 파일이나 데이터베이스에 저장될 데이터를 암호화합니다. 이 암호화는 파일의 내용 자체를 보호하여, 만약 파일 시스템이나 데이터베이스가 침해되더라도 데이터의 기밀성이 유지되도록 합니다. 이 단계에서는 데이터가 아직 압축되지 않은 원본 상태일 수 있습니다.

- 전송 계층(Transport Layer): TLS/SSL과 같은 프로토콜을 사용하여 데이터 전송 자체를 암호화합니다. 이 경우, 애플리케이션 계층에서 암호화된 데이터든 아니든, 네트워크를 통해 전송되는 모든 데이터는 암호화됩니다. 이때 TLS/SSL 설정에서 압축 기능을 비활성화하여 압축 오라클 공격을 방지할 수 있습니다.

- 파일 시스템/스토리지 계층(File System/Storage Layer): 디스크 암호화(예: BitLocker, dm-crypt)를 사용하여 저장된 데이터를 암호화합니다. 이는 물리적인 디스크가 도난당하더라도 데이터가 보호되도록 합니다. 이 계층에서의 압축은 일반적으로 성능상의 이유로 잘 사용되지 않습니다.

이러한 방식으로 각 계층이 자신의 보안 목표를 독립적으로 달성한다면, 한 계층에서의 압축 여부가 다른 계층에서의 암호화 보안에 영향을 미치는 문제를 최소화할 수 있습니다. 예를 들어, 데이터베이스에 저장할 중요한 정보는 애플리케이션 단에서 암호화하고, 웹 서버에서 클라이언트로 전송될 때는 TLS/SSL 암호화를 사용하되 압축은 비활성화하는 식입니다. 이렇게 하면 데이터의 기밀성과 무결성을 다중 방어(Defense in Depth) 관점에서 확보할 수 있습니다.

솔트(Salt)를 이용한 패스워드 해싱: 안전한 패스워드 관리

사용자 패스워드를 안전하게 저장하는 것은 데이터 침해 시 사용자 계정을 보호하는 데 매우 중요합니다. 해시 함수를 사용하는 주된 이유는 패스워드가 유출되더라도 원본 패스워드를 알아내기 어렵게 만들기 위함입니다. 해시는 단방향성과 빠른 연산 속도라는 특징을 가지고 있습니다.

하지만 단순히 패스워드를 해시하는 것만으로는 충분하지 않습니다. 다음과 같은 공격들이 존재하기 때문입니다.

1. 패스워드 크래킹 공격

- 사전 공격(Dictionary Attack): 미리 준비된 일반적인 단어나 구문 목록(사전 파일)을 해시하여 데이터베이스에 저장된 해시값과 비교하는 공격입니다.

- 무차별 대입 공격(Brute-Force Attack): 특정 길이의 모든 가능한 문자 조합을 시도하여 해시값을 비교하는 공격입니다. 계산 비용이 매우 높지만, 충분한 시간과 자원이 있다면 결국 성공할 수 있습니다.

- Lookup Table 공격: 해커가 미리 수많은 예상 패스워드에 대한 해시값을 계산해 놓은 테이블을 사용하여 데이터베이스에서 유출된 해시값을 빠르게 찾아 원본 패스워드를 알아내는 방법입니다.

- Reverse Lookup Table: 유출된 데이터베이스에서 계정 ID와 해시된 패스워드를 기반으로 룩업 테이블을 만든 후, 공격자가 추측한 패스워드의 해시값을 이 테이블에서 찾아 사용자와 패스워드를 매핑하는 방식입니다.

- 레인보우 테이블(Rainbow Table): 룩업 테이블의 저장 공간 문제를 해결하기 위해 고안된 기술입니다. 해시값과 원본 문자열의 “체인(chain)”을 미리 계산하여 저장해두고, 이를 통해 공격 시 필요한 연산량을 줄여 원본 패스워드를 빠르게 찾아냅니다. 이는 시간-공간 트레이드오프(Time-Space Trade-off) 기법의 한 예시입니다.

이러한 공격들은 패스워드 크래킹을 더 쉽고 빠르게 만듭니다. 우리는 이러한 공격들을 완전히 막을 수는 없지만, 그 효과를 현저히 떨어뜨릴 수 있습니다.

2. 솔트(Salt) 추가: 해싱 보안 강화

단순히 패스워드를 해시하는 방식의 취약점을 보완하기 위해 솔트(Salt)라는 임의의 데이터를 추가하여 해싱합니다. 솔트는 암호화할 필요가 없으며, 존재 자체만으로 위에서 언급된 룩업 테이블 및 레인보우 테이블 공격을 무력화하는 데 매우 효과적입니다. 솔트는 패스워드 앞에 붙이거나 뒤에 붙이거나 하는 방식보다는, 해시 함수 내부적으로 안전하게 처리되도록 설계된 키 유도 함수(KDFs)를 사용하는 것이 좋습니다.

잘못된 솔트 사용 방식

- 솔트 재사용(Salt Reuse): 동일한 솔트를 여러 사용자에게 사용하거나, 한 사용자의 패스워드가 변경되어도 솔트를 재사용하는 것은 매우 위험합니다. 이는 레인보우 테이블 공격이 다시 가능해지거나, 여러 계정의 패스워드를 동시에 크랙할 수 있게 만듭니다. 랜덤 솔트는 반드시 사용자 계정을 생성하거나 패스워드를 변경할 때마다 새로 생성되어야 합니다.

- 짧은 솔트(Short Salt): 솔트의 길이가 너무 짧으면 공격자가 모든 가능한 솔트 값에 대한 룩업 테이블을 쉽게 생성할 수 있습니다. 솔트는 최소한 사용하는 해시 함수의 출력 길이(예: SHA-256의 경우 256비트, 32바이트)와 같거나 그보다 길어야 합니다.

- 이중 해싱 및 비정상적인 해시 함수(Double Hashing & Wacky Hash Functions): 여러 해시 알고리즘을 섞어 쓰거나, 검증되지 않은 복잡한 방식으로 해싱하는 것이 더 안전할 것이라고 생각할 수 있습니다. 그러나 이는 오히려 예측 불가능한 취약점을 만들거나, 단지 공격자가 분석하는 데 약간의 시간을 더 소모하게 할 뿐 근본적인 보안 강화에 기여하지 못합니다. 잘 설계되고 검증된 표준 해시 알고리즘과 권장되는 키 유도 함수(PBKDF2, bcrypt, scrypt 등)를 올바른 사용법에 따라 사용하는 것이 가장 안전하고 효율적입니다.

올바른 솔트 사용 방식

안전한 솔트 생성: 솔트를 생성할 때는 단순한 의사 난수 생성기(Pseudo-Random Number Generator, PRNG)가 아닌, 암호학적으로 안전한 의사 난수 생성기(CSPRNG: Cryptographically Secure Pseudo-Random Number Generator)를 사용해야 합니다.

사용자별, 패스워드별 고유성: 솔트는 각 사용자 및 패스워드마다 고유(unique)해야 합니다. 사용자가 계정을 생성하거나 패스워드를 변경할 때마다 새로운 랜덤 솔트를 생성해야 합니다. 이 솔트는 최소한 해시 다이제스트보다 커야 합니다.

솔트 저장: 생성된 솔트는 해당 사용자의 해시된 패스워드와 함께 사용자 데이터베이스에 저장되어야 합니다. 솔트는 비밀 정보가 아니므로 암호화할 필요는 없습니다.

패스워드 검증: 사용자가 로그인 시 입력한 패스워드를 검증하기 위해, 데이터베이스에서 해당 사용자의 솔트와 해시값을 가져옵니다. 그 다음 입력된 패스워드에 가져온 솔트를 적용하여 해시하고, 이 결과값을 데이터베이스에 저장된 해시값과 비교합니다.

서버 측 해싱: 웹 애플리케이션에서 패스워드 해싱은 항상 서버 측에서 수행해야 합니다. 클라이언트 측(예: JavaScript)에서 패스워드를 해시하여 전송하더라도, 이는 HTTPS와 같은 안전한 전송 채널을 대체할 수 없으며 공격자가 클라이언트 측 해시 결과를 가로챌 경우 공격에 취약해질 수 있습니다. 또한 모든 브라우저가 클라이언트 측 스크립트를 지원하지 않을 수 있습니다.

키 스트레칭(Key Stretching): 동일한 해시 함수를 수천, 수만 번 반복하여 다이제스트를 생성하는 기법을 키 스트레칭이라고 합니다. 이는 패스워드 해싱에 대한 무차별 대입 공격의 비용을 기하급수적으로 증가시킵니다.

- 반복 횟수 설정: 반복 횟수는 웹 서버의 리소스를 과도하게 소모하지 않으면서(예: 0.2초 이내) 공격자가 효과적인 공격을 수행하기 어렵게 만드는 적절한 수준으로 설정해야 합니다. 이 반복 횟수는 시간이 지남에 따라 하드웨어 성능이 향상되므로 주기적으로 늘려야 합니다.

- 전문 라이브러리 사용: 직접 키 스트레칭 알고리즘을 구현하기보다는 검증된 암호화 라이브러리가 제공하는 함수(예:

PBKDF2_HMAC_SHA256함수와 반복 횟수 설정)를 사용하는 것이 안전합니다.

하드웨어 보안 모듈(HSM) 활용:

YubiHSM과 같은 하드웨어 보안 모듈(HSM: Hardware Security Module)을 사용하여 비밀 키를 안전하게 관리하고 해싱 작업을 수행하면, 소프트웨어적인 방법만으로는 어려운 강력한 해시 크래킹 방어 기능을 제공할 수 있습니다. HMAC과 같은 알고리즘을 사용할 때도 비밀 키 관리가 중요하며, HSM은 물리적으로 키를 보호하는 데 유용합니다.HSM이 소프트웨어보다 강력한 해시 크래킹 방어 기능을 제공하는 이유:

HSM은 암호화 키를 생성, 저장 및 보호하고 암호화 연산을 수행하기 위해 특별히 설계된 물리적 장치입니다. 소프트웨어 기반 솔루션과 비교할 때 다음과 같은 측면에서 더 강력한 보안을 제공합니다.

- 물리적 보안: HSM은 변조 방지(Tamper-resistant) 및 변조 감지(Tamper-evident) 기능을 갖추고 있어 물리적인 공격으로부터 키를 보호합니다. 키가 물리적으로 장치 내부에 격리되어 있어, 소프트웨어 공격으로는 접근하기 매우 어렵습니다. 반면 소프트웨어 기반 키는 운영체제 메모리나 디스크에 저장될 수 있어, 시스템 침해 시 탈취될 위험이 더 큽니다.

- 키 노출 방지: HSM 내에서 키가 생성되고 사용되며, 키가 HSM 외부로 절대로 노출되지 않도록 설계됩니다. 이는 “Zero-Exposure” 원칙으로, 공격자가 아무리 시스템을 침해하더라도 메모리 덤프나 다른 소프트웨어 기법으로 키를 추출할 수 없게 만듭니다. 해시 연산에 사용되는 비밀 키 또한 HSM 내부에 안전하게 보관되어 무단 접근을 차단합니다.

- 성능 및 전용 하드웨어: HSM은 암호화 연산에 최적화된 전용 하드웨어를 포함하고 있어, 일반 서버 CPU에서 소프트웨어적으로 처리하는 것보다 훨씬 빠르고 효율적인 암호화 및 해시 연산을 수행할 수 있습니다. 이는 높은 부하의 시스템에서도 보안 성능을 유지하는 데 중요합니다.

- 인증 및 규정 준수: HSM은 엄격한 보안 표준(예: FIPS 140-2)을 준수하도록 설계 및 인증되는 경우가 많습니다. 이는 금융, 정부 등 규제 준수가 중요한 환경에서 필수적입니다.

- 보안 감사 및 로깅: HSM은 키 사용 및 접근에 대한 상세한 보안 로그를 생성하여 감사 추적을 가능하게 합니다.

이러한 이유로 HSM은 특히 민감한 데이터를 다루거나 매우 높은 수준의 보안이 요구되는 환경에서 소프트웨어 기반의 키 관리 및 해시 연산을 대체하거나 보완하는 강력한 솔루션으로 활용됩니다.

일정한 시간 비교(Constant-Time Comparison): 해시값을 비교할 때, 비교 함수가 일정한 시간(constant-time)이 소요되도록 구현해야 합니다. 이는 시간 공격(Timing Attack)을 방어하기 위함입니다. 만약 비교 함수가 바이트별로 비교하여 일치하지 않는 부분이 발견되는 즉시 연산을 중단한다면, 공격자는 각 바이트가 일치하는 데 걸리는 시간을 측정하여 패스워드를 조금씩 추론할 수 있습니다.

memcmp와 같은 표준 라이브러리 함수 중 일부는 일정한 시간 비교를 보장하지 않을 수 있으므로, 암호학적으로 안전한constant-time comparison함수를 사용해야 합니다.